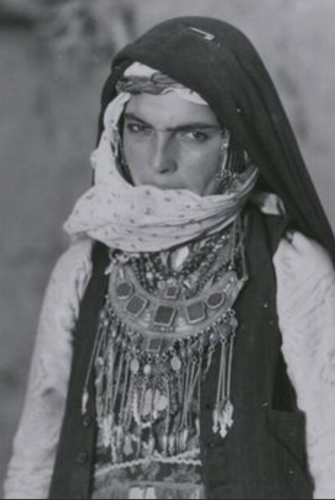

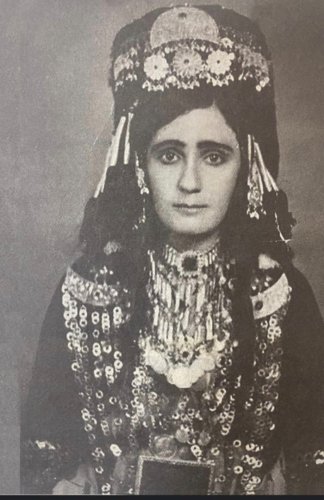

Despite the difficulties of life and natural inequalities, Kurdish women, in addition to paying attention to clothes, always paid attention to jewelry (which are accessory) and they would not forget to wear it even if they were only a little. The value of the gold and ornaments they used generally depended on the people's financial means. Naturally, the richer one was, the more valuable accessories they could use. Generally, Kurdish women's accessories included bracelets, earrings, anklets, and nose rings (1), which have rarely been used. (2) According to Pfeiffer, the use of small nose rings among women was common more or less. (3) In one of the Kurdish folklore songs collected by Thomas Bois, a beautiful woman asks a jeweler to carve a golden flower nose ring in her left nostril like Kurdish women (4), this suggests that nose ring was one of the most common accessories among Kurdish women.

In the comments of the tourists, although some examples of accessories and cosmetics are mentioned briefly, these materials can be useful to some extent to recreate the image of what Kurdish women used in the past. George Fowler described Kurdish women's desire for accessories as strings of coins that they tied to their necks and other parts of their bodies. (5) In his travelogue Walter Harris visited the East part of Kurdistan and reported that Kurdish women wore long strings of silver coins that covered their foreheads. (6) In another part of his journey, he sees the wife of the Kurdish leader adorned with coins of the kings of England, Napoleon and Turkish liras attached to her head and around her neck, (7) Fowler described their scarves being decorated with black strings around their heads, and ornamented by heavy silver coins and strings which were a part of their Shadas (a kind of Kurdish scarf). (8)

Similar to Fowler and Harris, Eugene Uben described the jewelry and accessories of Kurdish women in their Kurdish dance ceremonies like this: "large gold rings hang from their ears, and a necklace made of coins is attached to their head-dresses and passed under their chins. They tie another one around their foreheads." (9) Uben's report describes the type of jewelry as well as how they were used, the necklace that is worn under the chin is called Jerchanaga or Jerchana (9) which is mostly worn for wedding ceremonies.

Claudius James Rich referred to the jewelry of the wives of the nobility and the common people and wrote his report: "Wives of the lords wear a piece of accessory in front of their foreheads consisting of rows of gold leaf pendants and on both sides of the headscarf, a string of corals is hanged, which are tied together and tied to the accessory on their foreheads. They have very few gems; their accessories are generally made of gold and coral; lower-class women wear silver coins, small metal pieces and glass beads on their heads." (10) John Otter's report on the description of a Kurdish girl's accessories around Kermashan reveals that the type of accessories was a factor in distinguishing the social classes: "an iron ring, two centimeters wide, was hung from one of her nostrils, such rings were used as accessories. The rings of the rich were made of gold or silver." (11) In Hawraman, wealthy women and men used to decorate their hats called Kilaw Fes (12) with coral and blue beads or gold beads. (13)

According to Son, Nikitin talks about the accessories of Mukeriyani and Ardalani women: "Their earrings and bracelets and some gold strings that were attached to their foreheads are a part of their clothes." (14) The use of money in their accessories is very noticeable, Nikitin says: "money is rarely involved in Kurdish transactions and gold coins are used mainly as accessories to decorate Kurdish women's clothes and bodies." (15)

Little is known about Kurdish women's makeup, but what is available suggests that makeup is common among Kurdish women. In the book of Kurdish Customs and Traditions, it is mentioned that: "Kurdish women make up their hands, faces, cheeks and lips more like Arab women." (16)

Eugene Uben talks about Kurdish women's makeup like this in dancing ceremonies: "The cheeks are smeared with blush; the eyebrows are joined together by a black line." (17)

Clara Colliver Rice (18) wrote about the hairstyle of a Kurdish girl as the following: "She usually wore Kurdish clothes. She combed her hair into ten or twelve strands and placed a silk rosary at the end of each strand that reached down to her waist; what she wore looked more like a hat rather than a Charshew (a black veil worn by Muslim women), and it was tied over with turquoise to her head. Part of her hair was cut in a slant that stuck to the top of her head." (19)

According to tourists' comments, one of the other accessories and cosmetic things among Kurdish women (20) was "tattoos". The shape of a tattoo was carved on the body with a needle (21), and these patterns were fixed with black soot (22), Mohammad Bakir explained how they used to tattoo their bodies: "tattooing varies from one region to another. Many of us have seen people applying rubber bands of soot to the target area and carve it with a needle, until the color appears, however, in some areas such as Kobane and Sinjar, the bark of some trees is mixed with the milk of a mother who has given birth to a daughter and carving it with needles until the color would appear; of course, this process often has more than one stage."

In Ali Asghar Shamin's book, Kurdistan, tattooing is described as a form of makeup for Kurdish women which was painted in the form of wildflowers and leaves on their hands, feet, and arms. (23) In Kurdish literature, poems and folklore in the verses that describe the lover's tattoos or pimples, it is a direct mention of tattooing. It is clear that after Islam was established, the Kurds abandoned this tradition like many others (24).

Sources and Notes:

1. Nose rings.

2. Mahmoudi, Faraj Allah (1973), The Geography of Qorveh_Bijar_Diwandareh, Tehran, Bi Na.

3. Pfeiffer/ ida (1850)/ Eine Frauenfahrt um die welt/ band 3/ wien/ Verlag von carl Gerold. : 190

4. Bois, Thomas (1966), The Kurds, Published by Khayat Book & Publishing Company S.A.L. 90-94 Rue Bliss, Beirut, Lebanon. 116_115.

5. Fowler, George (1841), Three years in Persia; with traveling adventures in Koordistan, v2, London, Henry Colburn, Publisher. V2/: 24.

6. Harris/B. Walter (1896)/ from Batum to Baghdad: Via Tiflis/ Tabriz/ And Persian Kurdistan/ William Blackwood and Sons/ Edinburgh and London: 198

7. Harris/B. Walter (1896)/ from Batum to Baghdad: Via Tiflis/ Tabriz/ And Persian Kurdistan/ William Blackwood and Sons/ Edinburgh and London: 237

8. Pfeiffer/ ida (1850)/ Eine Frauenfahrt um die welt/ Band3/ wein/ Verlag von carl Gerold. 189_190.

9. Uben, Eugine (1983), Travelogue and Investigations of the French Ambassador in Iran, Today's Iran 1906_1907 Iran and Mesopotamia, translation and interpretation Ali Asghar Saeedi, first edition, Tehran, Zuvar Bookstore.

10. From the Kurdish dictionary of Hanbana Borina, there are three definitions for the entity of Jerchanaga: 1. A piece of jewelry that is tied under the chin. 2. A shawl. 3. Double chin. (Sharafkani, 1990: 402).

11. Rich, Claudius James (2019), Travelogue of Claudius James Rich (Kurdistan Chapter), Translated by Hassan Jaff, edited by Faramarz Aghabeigi, first edition, Tehran, Iranshenasi Publication, p. 231.

12. John Otter, (1984) John Otter's travelogue (Nader Shah's era), translated by Ali Eghbali, first edition, Bi ja, Javidan publication company. P.181.

13. This word has been mentioned in Kurdish poems.

14. Daneshwar, Mahmoud (2008), Iran's sceneries and stories, first edition, Tehran, Donyaye Ketab publication. P. 731.

15. Nikitin, Monsieur B (1978), Monsieur Nikitin's memories and travelogue, translated by Ali Mohammad Frahwashi (translator Homayoun), along with a preface written by Malek Al Sho'ara Bahar and Bahram Farahwashi, second edition, Tehran, Kanoon Ma'refat publisher. P. 215.

16. Nikitin, Monsieur B (1978), Monsieur Nikitin's memories and travelogue, translated by Ali Mohammad Frahwashi (translator Homayoun), along with a preface written by Malek Al Sho'ara Bahar and Bahram Farahwashi, second edition, Tehran, Kanoon Ma'refat publisher. P. 141.

17. Afandi Bayazidi Mahmoud (1990) Kurds' Customs and Traditions collected by the famous Russian orientalist Alexander Jaba, along with a preface and a conclusion written by Abdul Rahman Sharafkandi "Hajar", translated and interpreted by: Aziz Mohammadpour Dashbandi, first edition, Bi Ja, Bi Na, p.158.

18. Uben, Eugine (1983), Travelogue and Investigations of the French Ambassador in Iran, Today's Iran 1906_1907 Iran and Mesopotamia, translation and interpretation Ali Asghar Saeedi, first edition, Tehran, Zuvar Bookstore, p.116.

19. Rice/ Claudius James. Narrative of A Residence in Koordistan and on the site of ancient Nineveh with journal of a voyage down the Tigris to Baghdad, two volumes-Vol I, London: James Duncan, Paternoster Row, Edited by: his window.

20. Rice, Clara Colliver (2004), Iranian Women and their way of life (Clara Colliver Rice travelogue), translated by Asad Allah Azad, first edition, Tehran, Ketabdar publication. P.46.

21. Razm Ara has reported that men also used to tattoo their bodies. (Razm Ara, 1941: A/21) the shapes were different from each other.

22. DE Morgan, John Jack Mari du (2019), De Morgan's travelogue, Kazem Vadi'I's translation, Vol II, Tehran, Donyayeh Ketab. 57_ 2/58.

23. Shamim, Ali Asghar (1991), Kurdistan, first edition, Bi Ja, Modabber publication. P:52.

24. Agha Beigi, Faramarz (2021), Kurds within travelogues (from the Safavids to the end of the Pahlavi), first edition, Tehran, Iranshenasi publication.